Over 500 Science and History Articles Absolutely Free

We made all 5th grade reading level versions of our curriculum free and they're ready to be used in your classrooms.

Evidence for Evolution: Analogous and Homologous Structures

fossil record, homologous structure, analogous structure, vestigial structure, evolution

Evolution Unit

The evidence for evolution is deep and far-reaching. When they look at every level of organization in living systems, biologists see the mark of past and present changes. A large part of Darwin's book, On the Origin of Species, found patterns in the world around us that make sense with evolution. Since the time of Darwin, what we know has become clearer and broader. Evolution is when living things adapt over time to their environments in ways that help them live long enough to reproduce. This causes entire groups of living things to change because the parents pass on what helped them live to their children.

Fossils

Fossils give strong evidence that livings things from the past are not the same as those found today because they show a progression of evolution. Scientists figure out the age of fossils, or remains, and sort them all over the world to decide when the life forms lived in relationship to each other. The fossil record that comes from this is made up of all the fossils that have been found to tell a story of the past and show the evolution of form over millions of years.

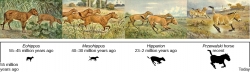

Fossil records with a lot of detail have been found for sequences of species in the evolution of whales and modern horses. The fossil record of horses in North America is quite rich. Many have transition fossils. These show anatomy that is in between earlier and later forms. The record goes back to a dog-like ancestor some 55 million years ago that gave rise to the first horse-like species 55 to 42 million years ago in the genus Eohippus. This group of remains shows the change in anatomy that came from drying over time that changed the landscape from a forest to a prairie. Fossils that followed show the change over time of teeth shapes and how the leg and foot are built for a habit of eating grass with changes for running from animals that may eat them. This happened with a species of Mesohippus found from 40 to 30 million years ago. Later species showed gains in size, such as those of Hipparion, which was around from about 23 to 2 million years ago. The fossil record shows several adaptations in the horse lineage. It is now only one genus, Equus, with several species.

A set of paintings on a timeline from 55 million years ago to today showing 4 of the ancestors to the horses of the present.

The first painting is of Eohippus, which lived from 55 to 45 million years ago. It was a small animal that was the size of a dog with 4 toes on the front feet and 3 on the back, a long tail, and a brown coat with spots. The second is Mesohippus, which lived from 40 to 30 million years ago. It was a bit larger than Eohippus with longer legs. It had 3 toes on the front and back feet. The third is Hipparion, which lived from 23 to 2 million years ago. It walked on its middle toe on each foot (now a hoof), but it still had hints of the remaining toes. It was much larger than Mesohippus. The fourth is Przewalski's horse, a recent but endangered horse. It is smaller and stockier than the domesticated horse with one toe (hoof) on each foot.

This drawing is of species that come from the remains of the evolutionary history of the horse. The species shown are only four from a very diverse line that has many branches, dead ends, and adaptive radiations. One of the changes shown here is from a forest to a prairie. This is shown in forms that are better for eating grasses and predator escape through running. Przewalski's horse is one of a few living species of horse.

Anatomy

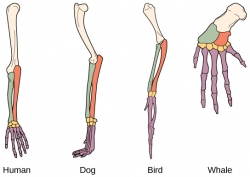

Another way to prove evolution is with structures in living things that share the same simple form. The bones in the limbs of a human, dog, bird, and whale all share the same overall way they are built. That similarity comes from their beginning in the appendages of a shared ancestor. Over time, evolution led to changes in the shapes and sizes of these bones in different species, but they have kept the same general layout. This shows that they came from a shared ancestor. These similar parts are called homologous structures. Some structures are present in living things that have no clear function at all and appear to be remaining parts from a past ancestor. Some snakes have pelvic bones even though they do not have legs because they came from reptiles that did have legs. Vestigial structures are parts left over in animals that do not have a clear job in the body. They come from a past ancestor that did use the body part at one time, but have not been lost because they do not hurt the animal’s ability to live. These kinds of structures are shown with wings on birds that cannot fly (which may have other jobs), leaves on some cacti, and the sightless eyes of cave animals.

This drawing compares a human arm, dog and bird legs and a whale flipper. All of these limbs have the same bones, but the size and shape of these bones can be different.

These limbs are built in a similar manner. This shows that these living things share an ancestor.

Similarity of Form

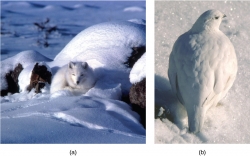

Another sign of evolution is the convergence of form in living things that share similar environments. Species of animals that are not related, such as the arctic fox and ptarmigan (a bird), live in the Arctic and have white coverings during winter to match with the snow and ice. The similarity happens not because of shared ancestors, indeed one covering is of fur and the other of feathers. They happened instead because of selection needs that are similar, such as the use of not being seen by predators.

Both the arctic fox and ptarmigan have evolved a color that helps them blend into their surroundings. They aren't related, but have evolved in a similar environment.

Two Measures of Similarity

Life forms that share similar physical features and genetic sequences are likely more closely related than those that do not. Characteristics that overlap both in form and genetically are referred to as homologous structures. The similarities stem from common evolutionary paths. As shown in the next image, the bones in the wings of bats and birds, the arms of humans, and the front leg of a horse are homologous structures. Notice the structure is not simply a single bone. Rather, it is a group of several bones put together in a similar way in each life form even though the parts of the structure may have changed shape and size.

Photo A shows a bird in flight with a drawing of bird wing bones. B shows a bat in flight with a drawing of bat wing bones. C shows a horse with a drawing of front leg bones. D shows a beluga whale with a drawing of flipper bones. E shows a human arm with a drawing of arm bones.

All the limbs share common bones, which is similar to the bones in the arms and fingers of humans. However, in the bat wing, finger bones are long and separate and form a scaffolding on which the wing's membrane is stretched. In the bird wing, the finger bones are united together. In the horse leg, the ulna is shorter and is fused to the radius. The hand bones are reduced to one long thick bone, and the finger bones are reduced to one long thick finger with a modified nail or hoof. In the whale flipper, the humerus and other bones are very short and thick.

Bat and bird wings, the front leg of a horse, the flipper of a whale, and the arm of a human are homologous structures, showing that bats, birds, horses, whales, and humans have a shared evolutionary past.

Misleading Appearances

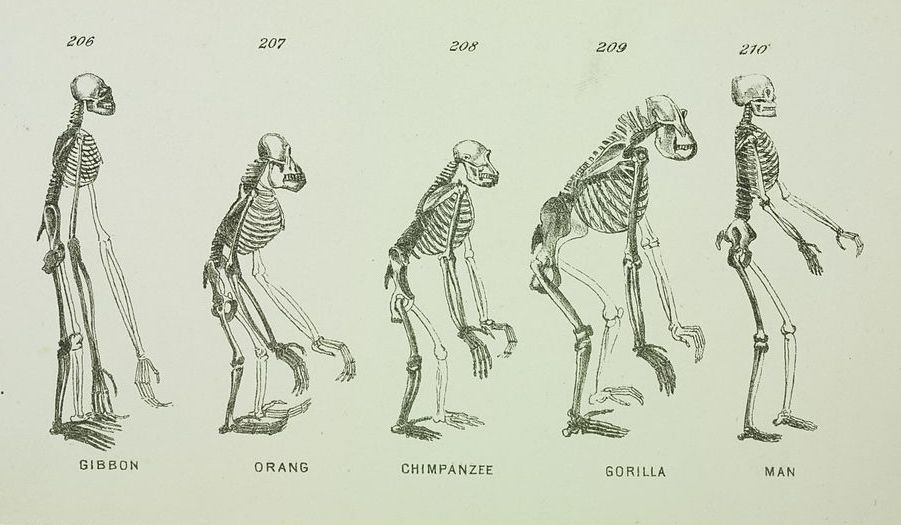

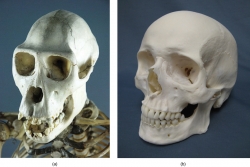

Some life forms may be very closely related, even though a minor genetic change caused a major morphological difference to make them look quite different. Chimpanzees and humans, the skulls of which are shown in the next image, share 99 percent of their genes. However, they show major anatomical differences, such as how much the jaw protrudes in the adult and the relative lengths of our arms and legs.

A chimpanzee skull and a human skull. Though we look different from the outside, we share 99% of the same genes.

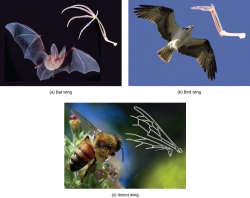

However, unrelated life forms may be distantly related yet appear very much alike, often because common adaptations to similar environmental conditions came about in both. An example is the streamlined body shapes, the shapes of fins and appendages, and the shape of the tails in fishes and whales, which are mammals. These structures have a surface-level similarity because they are adaptations to moving about in the same living space, water. When a characteristic that is similar occurs by adaptive convergence, and not because of a close evolutionary relationship, it is called an analogous structure. In another example, insects use wings to fly like bats and birds. We call them both wings because they have same function and have a similar form on the surface, but the embryonic origin of the two wings is quite different. The difference in the development, or embryogenesis, of the wings in each case is a signal that insects and bats or birds do not share a common ancestor that had a wing. The wing structures, shown in the next image, came about independently in the two lineages.

The wings of a bat, bird and bee all look fairly similar, but evolved in different ways to solve the same problem: flight.

Traits can be either homologous or analogous. Homologous traits share an evolutionary path that led to the making of that trait. Analogous traits do not share that path. Scientists must decide which kind of similarity a feature shows to figure out the phylogeny of the life forms being studied.