Once upon a time there was a boat full of rubber duckies. It set off to sail across the ocean from Asia to the United States of America. But then there was a bump, there was a splash, and the rubber duckies fell off the boat and into the water. Twenty-eight thousand rubber duckies lost at sea! What happened to all of them? This is a true story. It's the story of bath toys that helped us learn how our oceans move. Do not worry, no rubber duckies were hurt in the making of this article.

Wait a minute, where are you going? Now don't get carried away!

Kristen Wong, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The ocean is always moving. If you have ever dropped a toy or a hat into the waves, you know this. It will be pulled away by the water and carried far, far away. The little duckies figured this out too.

Surface current is any movement of the water that happens anywhere from the top of the ocean to three hundred feet deep. The water there moves mostly by the wind, which blows along the top, making ripples. When enough wind pushes the same way for a long time, it will make a wave. This energy stops when the wave breaks on a beach. Those ducks may have been lost, but at least some of them got to surf a little.

These guys made it to the surf.

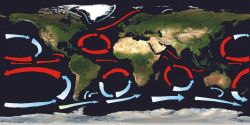

Did you know that the wind changes because the world turns? It would blow in a straight line, but because the world is turning under it, it ends up curving. What does this have to do with ducks and water? Out in the ocean, the wind will blow in great big circles, curving to the right on the top half of the Earth, and curving to the left on the bottom half of the world. A

gyre is when the spinning of the planet and the wind work together to push the water in the ocean in a large circle. Let's hope those rubber duckies really like the ocean, because some of them will float along the gyre they fell into for a long, long time.

Ocean gyres. Looks like a lot of running around in circles.

Diagram by NASA/Ingwik Land_shallow_topo_2048.jpg: NASAderivative work: Ingwik, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

So wind pushes the top of the water. How does water move below the surface? I wish I could tell you it were as simple as whale fins pushing it along.

Deep ocean currents are any water movements that happen 300 feet below the top of the water and they are due to how much salt is in the water. Have you ever tried to drink from the ocean? I hope not. It's very salty. Some parts of the ocean are saltier than others. When the sun shines down, it pulls some water into the air, leaving that part of the ocean saltier. The salt makes that water heavy, and it sinks. When that happens, warmer water from below rises up. That sinking and rising motion is enough to get things moving beneath the waves.

That's it? Salt? So this water cannot be that strong, right? Well, have you ever seen a rushing river? The water under the waves is sixteen times as strong! Luckily the little rubber ducks are good floaters. The

global conveyer belt is a strong underwater current that moves all over the world. Think of it like the strip that pulls your groceries along at the checkout counter. It starts by the North Pole where the icy water does not have much salt. It goes down past North and South America to Antarctica. Then it breaks into two paths, one going to the Indian Ocean and one to the Pacific Ocean. Finally, they both end up back on each end of the Atlantic. Some of these little ducks have gone farther than any of us ever will!

Some rubber duckies went so far they grew along the way.

So what happened to the rubber duckies? They are still showing up! They have washed up everywhere from America to China to Great Britain! Some have been found frozen in the ice in the north. Some have been found still in the ocean on the other ends of the world. Who would have thought that they could teach us so much about how our oceans move? Maybe young scientists should not turn in their rubber duckies for a microscope just yet.

References:

Horton, Jennifer. "How do

ducks float?" HowStuffWorks.com, 2008

<http://animals.howstuffworks.com/birds/duck-float.htm>

Kids Geo. "Ocean Currents" Kids Geo, 2009. <

http://www.kidsgeo.com/geography-for-kids/0145-ocean-currents.php>

Horton, Jennifer. "How Ocean

Currents Work" HowStuffWorks.com, 2008. <http://science.howstuffworks.com/environmental/earth/oceanography/ocean-current.htm>